Rothschild of Moscow Daughter, Prima of Imperial Russian Ballet medal Judaica

Portrait of Polyakov by K. Died 1914 was a Russian-Jewish entrepreneur. Polyakov founded his first bank in 1872 and by the 1890s owned an influential financial group; he was informally named Rothschild.

His business collapsed in the early 1900s and was completely disbanded by 1909. Lazar and his brothers, future railroad magnate. Were born into the family of a small trader in. Lazar's grandfather had moved from. Version of "Polyak", which means Pole.

Lazar remained in the shadow of his better-known brother and employer Samuel until 1872, when he founded. In the 1870s and 1880s Polyakov founded five more commercial banks in Moscow, Oryol. And two mortgage banks Moscow, Yaroslavl. He remained the principal shareholder and manager of these banks until their collapse in the 1900s. The assets of his top level holding companies were valued at 40 million roubles, mostly in the stock of his own enterprises.His business rarely ventured into the textiles, metalworking and real estate that were the fields of traditional Moscow bankers. However, the Jewish sources point at the rivalry between Polyakov and ethnic Russian bankers represented by the mayor of Moscow Nikolay Alekseyev. Polyakov's International Moscow Bank building in Kuznetsky Most. Polyakov instructed the architect, Semyon Eybushitz.

To recreate the San Spirito Bank. Polyakov's continuing practice of relying on the inflated value of his own stock used as collateral contributed to his own demise. It started with Yakov Polyakov's bank problems in 1898. Then in 1901 Yakov's Peterburg-Azov Bank collapsed beyond recovery. Recession of the 1900s brought the stock prices down.Polyakov defaulted on his loans and his banks folded one by one. The Ministry of Finance, fearing a domino effect.

Initially supported Polyakov's banks. However, as the crisis developed the banker himself became an obstacle to restructuring. In 1909 the Ministry of Finance took over the last three surviving banks and consolidated them into a new United Bank Russian. The three banks declared 25 million roubles in assets of which 17.5 million were written off as bad debt. United Bank was chaired by an ethnic Russian appointed by the government, while Polyakov's son Alexander retained a seat on the board of directors.

In the end, Lazar's own finances were ruined to the extent that his own sons refused to take up his debt-ridden estate upon his death. Lazar Polyakov remained the leader of Moscow Jewish community for 35 years, and has been the main sponsor of Moscow Choral Synagogue. Prior to its completion in 1906, Polyakov allowed the congregation to pray in his own house.

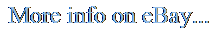

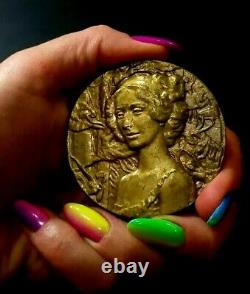

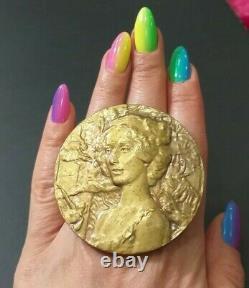

Mase said in the funeral eulogy. That his name is retold in fairytales across the pale of settlement. Our poorer brethren, blessing themselves on their wedding days, say'Let G-d make you equal to Polyakov. 23 January 1931 (aged 49). Lyubov Feodorovna Pavlova Matvey Pavlovich Pavlov. , born Anna Matveyevna Pavlova Russian.31 January 1881 - 23 January 1931, was a Russian prima ballerina. Of the late 19th and the early 20th centuries. She was a principal artist of the Imperial Russian Ballet. Pavlova is most recognized for her creation of the role of The Dying Swan.

And, with her own company, became the first ballerina to tour around the world, including South America, India and Australia. Anna Matveyevna Pavlova was born in the Preobrazhensky Regiment. Where her father Matvey Pavlovich Pavlov served. Some sources say that her parents married just before her birth, others - years later. Her mother Lyubov Feodorovna Pavlova came from peasants and worked as a laundress at the house of a Russian-Jewish banker Lazar Polyakov. When Anna rose to fame, Polyakov's son Vladimir claimed that she was an illegitimate daughter of his father; others speculated that Matvey Pavlov himself supposedly came from Crimean Karaites. There is even a monument built in one of Yevpatoria. Dedicated to Pavlova, yet both legends find no historical proof.Anna Matveyevna changed her patronymic to Pavlovna when she started performing on stage. Students of the Imperial Ballet School in Marius Petipa's Un conte de fées. A ten-year-old Anna Pavlova participated in this work in her first ever ballet performance.

She is photographed here on the left holding the birdcage. Pavlova was a premature child. Regularly felt ill and was soon sent to the Ligovo.

Village where her grandmother looked after her. Pavlova's passion for the art of ballet. Took off when her mother took her to a performance of Marius Petipa.S original production of The Sleeping Beauty. At the Imperial Maryinsky Theater. The lavish spectacle made an impression on Pavlova. When she was nine, her mother took her to audition for the renowned Imperial Ballet School.

Because of her youth, and what was considered her "sickly" appearance, she was rejected, but, at age 10, in 1891, she was accepted. She appeared for the first time on stage in Marius Petipa. S Un conte de fées. (A Fairy Tale), which the ballet master staged for the students of the school. Young Pavlova's years of training were difficult.

Did not come easily to her. Her severely arched feet, thin ankles, and long limbs clashed with the small, compact body favoured for the ballerina of the time. Her fellow students taunted her with such nicknames as The broom and La petite sauvage. Undeterred, Pavlova trained to improve her technique.

She would practice and practice after learning a step. She said, No one can arrive from being talented alone. God gives talent, work transforms talent into genius. She took extra lessons from the noted teachers of the day- Christian Johansson. Considered the greatest ballet virtuoso of the time and founder of the Cecchetti method.

A very influential ballet technique used to this day. In 1898, she entered the classe de perfection of Ekaterina Vazem. Former Prima ballerina of the Saint Petersburg Imperial Theatres. During her final year at the Imperial Ballet School, she performed many roles with the principal company.She graduated in 1899 at age 18. Chosen to enter the Imperial Ballet a rank ahead of corps de ballet as a coryphée.

She made her official début at the Mariinsky Theatre in Pavel Gerdt's Les Dryades prétendues (The False Dryads). Her performance drew praise from the critics, particularly the great critic and historian Nikolai Bezobrazov. At the height of Petipa. S strict academicism, the public was taken aback by Pavlova's style, a combination of a gift that paid little heed to academic rules: she frequently performed with bent knees, bad turnout, misplaced port de bras and incorrectly placed tours. Such a style, in many ways, harked back to the time of the romantic ballet. And the great ballerinas of old. Pavlova performed in various classical variations. In such ballets as La Camargo. Marcobomba and The Sleeping Beauty. Her enthusiasm often led her astray: once during a performance as the River Thames in Petipa's The Pharaoh's Daughter.Her energetic double pique turns led her to lose her balance, and she ended up falling into the prompter's box. Her weak ankles led to difficulty while performing as the fairy Candide in Petipa's The Sleeping Beauty, leading the ballerina to revise the fairy's jumps en pointe, much to the surprise of the Ballet Master. She tried desperately to imitate the renowned Pierina Legnani.

Prima ballerina assoluta of the Imperial Theaters. Once, during class, she attempted Legnani's famous fouettés. Causing her teacher, Pavel Gerdt, to fly into a rage. It is positively more than I can bear to see the pressure such steps put on your delicate muscles and the severe arch of your foot. I beg you to never again try to imitate those who are physically stronger than you. You must realize that your daintiness and fragility are your greatest assets. You should always do the kind of dancing which brings out your own rare qualities instead of trying to win praise by mere acrobatic tricks.Pavlova rose through the ranks quickly, becoming a favorite of the old maestro Petipa. It was from Petipa himself that Pavlova learned the title role in Paquita. Princess Aspicia in The Pharaoh's Daughter, Queen Nisia in Le Roi Candaule, and Giselle. She was named danseuse in 1902, première danseuse in 1905, and, finally, prima ballerina in 1906 after a resounding performance in Giselle. Petipa revised many grand pas.

For her, as well as many supplemental variations. She was much celebrated by the fanatical balletomanes of Tsarist Saint Petersburg, her legions of fans calling themselves the Pavlovatzi. When the ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska.Was pregnant in 1901, she coached Pavlova in the role of Nikiya in La Bayadère. Kschessinska, not wanting to be upstaged, was certain Pavlova would fail in the role, as she was considered technically inferior because of her small ankles and lithe legs. Instead, audiences became enchanted with Pavlova and her frail, ethereal look, which fitted the role perfectly, particularly in the scene The Kingdom of the Shades. Anna Pavlova in the Fokine/Saint-Saëns The Dying Swan. Pavlova is perhaps most renowned for creating the role of The Dying Swan.

A solo choreographed for her by Michel Fokine. The ballet, created in 1905, is danced to Le cygne. From The Carnival of the Animals.

Pavlova also choreographed several solos herself, one of which is The Dragonfly, a short ballet set to music by Fritz Kreisler. While performing the role, Pavlova wore a gossamer gown with large dragonfly wings fixed to the back.

Pavlova had a rivalry with Tamara Karsavina. According to the film A Portrait of Giselle. Karsavina recalls a wardrobe malfunction. During one performance, her shoulder straps fell and she accidentally exposed herself, and Pavlova reduced an embarrassed Karsavina to tears.

In the first years of the Ballets Russes. Pavlova worked briefly for Sergei Diaghilev. Originally, she was to dance the lead in Mikhail Fokine.

But refused the part, as she could not come to terms with Igor Stravinsky. S avant-garde score, and the role was given to Tamara Karsavina. All her life, Pavlova preferred the melodious "musique dansante" of the old maestros such as Cesare Pugni.

And cared little for anything else which strayed from the salon-style ballet music of the 19th century. Photographic postcard of Anna Pavlova as the Princess Aspicia in Alexander Gorsky's version of the Petipa/Pugni The Pharaoh's Daughter.

After the first Paris season of Ballets Russes, Pavlova left it to form her own company. It performed throughout the world, with a repertory consisting primarily of abridgements of Petipa's works, and specially choreographed pieces for herself. A very enterprising and daring act. She toured on her own... For twenty years until her death.She traveled everywhere in the world that travel was possible, and introduced the ballet to millions who had never seen any form of Western dancing. Pavlova also performed many'ethnic' dances, some of which she learned from local teachers during her travels. In addition to the dances of her native Russia, she performed Mexican, Japanese, and East Indian dances. Supported by her interest, Uday Shankar. Her partner in Krishna Radha (1923), went on to revive the long-neglected art of the dance in his native India.

In 1916, she produced a 50-minute adaptation of The Sleeping Beauty in New York City. Members of her company were largely English girls with Russianized names. In 1915, she appeared in the film The Dumb Girl of Portici. In which she played a mute girl betrayed by an aristocrat. After leaving Russia, Pavlova moved to London.

England, settling, in 1912, at the Ivy House on North End Road, Golders Green. Where she lived for the rest of her life. The house had an ornamental lake where she fed her pet swans, and where now stands a statue of her by the Scots sculptor George Henry Paulin. The house was featured in the film Anna Pavlova.It is now the London Jewish Cultural Centre. Marks it as a site of significant historical interest being Pavlova's home. While in London, Pavlova was influential in the development of British ballet, most notably inspiring the career of Alicia Markova.

The Gate pub, located on the border of Arkley. (London Borough of Barnet), has a story, framed on its walls, describing a visit by Pavlova and her dance company. There are at least five memorials to Pavlova in London, England: a contemporary sculpture by Tom Merrifield of Pavlova as the Dragonfly in the grounds of Ivy House, a sculpture by Scot George Henry Paulin. In the middle of the Ivy House pond, a blue plaque on the front of Ivy House, a statuette sitting with the urn that holds her ashes in Golders Green Crematorium, and the gilded statue atop the Victoria Palace Theatre.

When the Victoria Palace Theatre. In London, England, opened in 1911, a gilded statue of Pavlova had been installed above the cupola of the theatre. This was taken down for its safety during World War II. In 2006, a replica of the original statue was restored in its place. In 1928, Anna Pavlova engaged St. Petersburg conductor Efrem Kurtz to accompany her dancing, which he did until her death in 1931. During the last five years of her life, one of her soloists, Cleo Nordi.Another St Petersburg ballerina, became her dedicated assistant, having left the Paris Opera Ballet. In 1926 to join her company and accompanied her on her second Australian tour to Adelaide. Nordi kept Pavlova's flame burning in London, well into the 1970s, where she tutored hundreds of pupils including many ballet stars.

Anna Pavlova, 1915, Library of Congress. Between 1912 and 1926, Pavlova made almost annual tours of the United States, traveling from coast to coast. A generation of dancers turned to the art because of her.

She roused America as no one had done since Elssler. America became Pavlova-conscious and therefore ballet-conscious. Dance and passion, dance and drama were fused.

Pavlova was introduced to audiences in the United States. During his time as managing director of the Boston Grand Opera Company from 1914 to 1917 and was featured there with her Russian Ballet Company during that period. In 1914, Pavlova performed in St. Louis, Missouri, after being engaged at the last minute by Hattie B. Responsible for a series of worthy musical attractions presented to the St. Louis public during the season of 1913-14. Gooding went to New York to arrange with the musical managers for the attractions offered. Out of a long list, she selected those who represent the highest in their own special field, and which she felt sure St. The list began with Madame Louise Homer. Prima donna contralto of the Metropolitan Grand Opera Co.Pianist, and Anna Pavlova and the Russian ballet. The advance sales were greater than any other city in the United States.

At the Pavlova concert, when Gooding engaged, at the last hour, the Russian dancer for two nights, the New York managers became dubious and anxiously rushed four special advance agents to assist her. On seeing the bookings for both nights, they quietly slipped back to New York fully convinced of her ability to attract audiences in St. Louis, which had always, heretofore, been called "the worst show town" in the country.Her manager and companion, asserted he was her husband in his biography of the dancer in 1932: Anna Pavlova: In Art & Life Dandre 1932. They had secretly married in 1914 after first meeting in 1904 some sources say 1900. He died on 5 February 1944 and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium.

And his ashes placed below those of Anna. Victor Dandré wrote of Pavlova's many charity dance performances and charitable efforts to support Russian orphans in post- World War I. Who were in danger of finding themselves literally in the street. They were already suffering terrible privations and it seemed as though there would soon be no means whatever to carry on their education. Girls of America who made her an honorary member. During her life, she had many pets including a Siamese cat, various dogs, and many kinds of birds, including swans. Dandré indicated she was a lifelong lover of animals and this is evidenced by photographic portraits she sat for, which often included an animal she loved. A formal studio portrait was made of her with Jack, her favorite swan. " style="position: relative; margin: 0px auto; width: 170px;>. Anna Pavlova arriving in The Hague. The ashes of Anna Pavlova, above those of Victor Dandré, Golders Green Crematorium.While travelling from Paris to The Hague. Pavlova became very ill, and worsened on her arrival in The Hague. She sent to Paris for her personal physician, Dr Zalewski to attend her. She was told that she had pneumonia. She was also told that she would never be able to dance again if she went ahead with it.

She refused to have the surgery, saying If I can't dance, then I'd rather be dead. In the bedroom next to the Japanese Salon of the Hotel Des Indes in The Hague, twenty days short of her 50th birthday. Victor Dandré wrote that Pavlova died a half hour past midnight on Friday, January 23, 1931, with her maid Marguerite Létienne, Dr.

Zalevsky, and himself at her bedside. Her last words were, Get my'Swan' costume ready. Dandré and Létienne dressed her body in her favorite beige lace dress and placed her in a coffin with a sprig of lilac. In accordance with old ballet tradition, on the day she was to have next performed, the show went on, as scheduled, with a single spotlight circling an empty stage where she would have been. Memorial services were held in the Russian Orthodox Church.Pavlova was cremated, and her ashes placed in a columbarium. Where her urn was adorned with her ballet shoes (which have since been stolen).

Pavlova's ashes have been a source of much controversy, following attempts by Valentina Zhilenkova and Moscow mayor. To have them flown to Moscow for interment in the Novodevichy Cemetery. These claims were later found to be false, as there is no evidence to suggest that this was her wish at all.

The only documentary evidence that suggests that such a move would be possible is in the will of Pavlova's husband, who stipulated that, if Russian authorities agreed to such a move and treated her remains with proper reverence, then the crematorium caretakers should agree to it. Despite this clause, the will does not contain a formal request or plans for a posthumous journey to Russia. The most recent attempt to move Pavlova's remains to Russia came in 2001.

Golders Green Crematorium had made arrangements for them to be flown to Russia for interment on 14 March 2001, in a ceremony to be attended by various Russian dignitaries. This plan was later abandoned after Russian authorities withdrew permission for the move. It was later revealed that neither Pavlova's family nor the Russian Government.Had sanctioned the move and that they had agreed the remains should stay in London. Pavlova inspired the choreographer Frederick Ashton.

When, as a boy of 13, he saw her dance in the Municipal Theater in Lima. Is believed to have been created in honour of the dancer in Wellington during her tour of New Zealand and Australia in the 1920s. The nationality of its creator has been a source of argument between the two nations for many years. Known in English as the "Mexican Hat Dance", gained popularity outside of Mexico. When Pavlova created a staged version in pointe shoes.For which she was showered with hats by her adoring Mexican audiences. Afterward, in 1924, the Jarabe Tapatío was proclaimed Mexico's national dance. In 1980, Igor Carl Faberge licensed a collection of 8-inch full lead crystal wine glasses to commemorate the centenary of Pavlova's birth. The glasses were crafted in Japan under the supervision of The Franklin Mint. A frosted image of Pavlova appears in the stem of each glass.

Originally each set contained 12 glasses. Pavlova's life was depicted in the 1983 film Anna Pavlova. Pavlova's dances inspired many artworks of the Irish. The critic of The Observer. Wrote on 16 April 1911: Mr.Lavery's portrait of the Russian dancer Anna Pavlova, caught in a moment of graceful, weightless movement... Her miraculous, feather-like flight, which seems to defy the law of gravitation.

Of the Dutch airline KLM. With the registration PH-KCH carried her name. It was delivered on August 31, 1995.

Pavlova appears as a character in Rosario Ferre. S novel Flight of the Swan. Pavlova appears as a character in the fourth episode of the British series Mr Selfridge. Played by real-life ballerina Natalia Kremen. Pavlova appears as a character, played by Maria Tallchief, in the 1952 film Million Dollar Mermaid.

Her feet were extremely arched, so she strengthened her pointe shoe. By adding a piece of hard leather on the soles for support and flattening the box of the shoe.

At the time, many considered this "cheating", for a ballerina of the era was taught that she, not her shoes, must hold her weight en pointe. In Pavlova's case, this was extremely difficult, as the shape of her feet required her to balance her weight on her big toes. Her solution became, over time, the precursor of the modern pointe shoe, as pointe work became less painful and easier for curved feet. S biography, Pavlova did not like the way her invention looked in photographs, so she would remove it or have the photographs altered so that it appeared she was using a normal pointe shoe.

At the turn-of-the-Twentieth century, the Imperial Ballet began a project that notated much of its repertory in the Stepanov method of choreographic notation. Most of the notated choreographies were recorded while dancers were being taken through rehearsals.After the revolution of 1917. This collection of notation was taken out of Russia by the Imperial Ballet's former régisseur Nicholas Sergeyev. Who utilized these documents to stage such works as The Nutcracker, The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake, as well as Marius Petipa's definitive versions of Giselle and of Coppélia for the Paris Opéra Ballet. And the Vic-Wells Ballet of London precursor of the Royal Ballet.

The productions of these works formed the foundation from which all subsequent versions would be based to one extent or another. Eventually, these notations were acquired by Harvard University. And are now part of the cache of materials relating to the Imperial Ballet known as the Sergeyev Collection.

That includes not only the notated ballets but rehearsal scores as used by the company at the turn-of-the-twentieth century. Pavlova is also included in some of the other notated choreographies when she participated in performances as a soloist. Several of the violin or piano reductions used as rehearsal scores reflect the variations that Pavlova chose to dance in a particular performance, since, at that time, classical variations were often performed ad libitum, i. At the dancer's choice. One variation, in particular, was performed by Pavlova in several ballets, being composed by Riccardo Drigo.

For Pavlova's performance in Petipa's ballet Le Roi candaule that features a solo harp. This variation is still performed in modern times in the Mariinsky Ballet's staging of the Paquita grand pas classique.

You can help by adding missing items. Pavlova's repertoire includes the following roles. "Anna Pavlova as a Bacchante", by Sir John Lavery. Stained glass window entitled El Jarabe Tapatio.

The Butterfly Costume Design by Léon Bakst. For Anna Pavlova, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.Rooftop statue of Anna Pavlova. Pavlova in La Fille mal gardée. Anna Pavlova in Paris, 1920s. Pavlova in The Dying Swan. This item is in the category "Coins & Paper Money\Exonumia\Medals".

The seller is "top-art-medals" and is located in this country: IL. This item can be shipped worldwide.