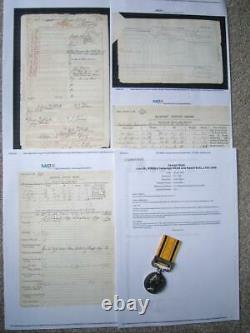

Victoria Zulu 1879 clasp war medal George Slack Royal Scots Fusiliers of Chester

George Slack born in Nantwich near Chester 1860, he attested for the 18th Brigade as 1420 Private aged 18 in February 1878 and soon transferred to the Royal Scots Fusiliers (2nd battalion 21st regt) in February 1879. He was posted to South Africa and fough the "Zulu" natives from Feb 1879 earning medal and clasp. He was tried by court martial for misconduct mid 1879 and served a number of weeks confinement. His conduct was considered latterly good since punishment July 1879.

Victoria Zulu 1879 clasp war medal George Slack Royal Scots Fusiliers of Chester. Victorian "Zulu Wars" 1879 South African Campaign medal.

Victorian Zulu war medal with 1879 Clasp , 2421. Fusrs (2nd Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers) correct official engraved name, IMO Extremely fine / Good very fine condition plus. It has minimal wear, clasp original, stamped out and not a cast copy (see photo of the back of date clasp, cast copies are flat), see pictures for condition.Supplied with copy of original medal roll extract confirms medal award and part attestation with military history, medal and 1879 clasp confirmed in attestation papers, (campaigns & medals section), also entitled to India General Service medal with Burma clasp 1885-87, see pictures for condition George Slack born in Nantwich near Chester 1860, he attested for the 18th Brigade as 1420 Private aged 18 in February 1878 and soon transferred to the Royal Scots Fusiliers (2nd battalion 21st regt) in February 1879. On 22 January 1879, Chelmsford established a temporary camp for his column near Isandlwana, but neglected to strengthen its defence by encircling his wagons. After receiving intelligence reports that part of the Zulu army was nearby, he led part of his force out to find them. Over 20,000 Zulus, the main part of Cetshwayo's army, then launched a surprise attack on Chelmsford's poorly fortified camp.

Fighting in an over-extended line and too far from their ammunition, the British were swamped by sheer weight of numbers. The majority of their 1,700 troops were killed. Supplies and ammunition were also seized. The Zulus earned their greatest victory of the war and Chelmsford was left no choice but to retreat. The Victorian public was shocked by the news that'spear-wielding savages' had defeated their army.After their victory at Isandlwana, around 4,000 Zulus pressed on to Rorkes Drift, where a small British garrison held them back for 12 hours. Although a welcome boost to British morale, the siege had little effect on the overall campaign. After Colonel Charles Pearson's right column defeated 6,000 Zulus at Nyezane, it occupied Eshowe station, but was then besieged by the Zulus for two months. Upon hearing news of the defeat at Isandlwana, Colonel Evelyn Wood's left column established a fortification near Khambula. His men were the only effective British force left in Zululand.

February Chelmsford began preparations for a second offensive into Zululand. The same day, news of the defeat at Isandlwana reached London and reinforcements were dispatched to South Africa. The new start of the larger, heavily reinforced second invasion of 1879 was not promising for the British. Despite their successes in March/ April at Kambula, Gingindlovu and Eshowe, they were right back where they had started from at the beginning of January. Nevertheless, Chelmsford had a pressing reason to proceed with haste Sir Garnet Wolseley was being sent to replace him, and he wanted to inflict a decisive defeat on Cetshwayo's forces before then.

With yet more reinforcements arriving, soon to total 16,000 British and 7,000 Native troops, Chelmsford reorganised his forces and again advanced into Zululand in June, this time with extreme caution building fortified camps all along the way to prevent any repeat of Isandlwana. One of the early British casualties was the exiled heir to the French throne, Imperial Prince Napoleon Eugene, who had volunteered to serve in the British army and was killed on 1 June while out with a reconnoitering party. Cetshwayo, knowing that the newly reinforced British would be a formidable opponent, attempted to negotiate a peace treaty.

Chelmsford was not open to negotiations, as he wished to restore his reputation before Wolseley relieved him of command, and he proceeded to the royal kraal of Ulundi, intending to defeat the main Zulu army. On 4 July, the armies clashed at the Battle of Ulundi, and Cetshwayo's forces were decisively defeated.Victorian "1st Boer war" - The Boer revolt in Transvaal. With the defeat of the Zulus, and the Pedi, the Transvaal Boers were able to give voice to the growing resentment against the 1877 British annexation of the Transvaal and complained that it had been a violation of the Sand River Convention of 1852, and the Bloemfontein Convention of 1854. Major-General Sir George Pomeroy Colley, after returning briefly to India, finally took over as Governor of Natal, Transvaal, High Commissioner of SE Africa and Military Commander in July 1880. Multiple commitments prevented Colley from visiting the Transvaal where he knew many of the senior Boers. Instead he relied on reports from the Administrator, Sir Owen Lanyon, who had no understanding of the Boer mood or capability.

Belatedly Lanyon asked for troop reinforcements in December 1880 but was overtaken by events. The Boers revolted on 16 December 1880 and took action at Bronkhorstspruit against a British column of the 94th Foot who were returning to reinforce Pretoria. At the first battle at Bronkhorstspruit on 20 December 1880, Lieutenant-Colonel Philip Anstruther and 120 men of the 94th Foot (Connaught Rangers) were killed or wounded by Boer fire within minutes of the first shots. Boer losses totalled two killed and five wounded. This mainly Irish regiment was marching westward toward Pretoria, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Anstruther, when halted by a Boer commando group.

They were halted when they approached a small stream called the Bronkhorstspruit, 38 miles from Pretoria. Its leader, Commandant Frans Joubert, ordered Anstruther and the column to turn back, stating that the territory was now again a Boer Republic and therefore any further advance by the British would be deemed an act of war. Anstruther refused and ordered that ammunition be distributed. The Boers opened fire and the ambushed British troops were annihilated.

In the ensuing engagement, the column lost 56 men dead and 92 wounded. With the majority of his troops dead or wounded, the dying Anstruther ordered surrender. The Boer uprising caught the six small British forts scattered around the Transvaal by surprise. They housed some 2,000 troops between them, including irregulars with as few as fifty soldiers at Lydenburg in the east which Anstruther had just left. Being isolated, and with so few men, all the forts could do was prepare for a siege, and wait to be relieved.

By 6 January 1881, Boers had begun to besiege Lydenburg. The other five forts, with a minimum of fifty miles between any two, were at Wakkerstroom and Standerton in the south, Marabastad in the north and Potchefstroom and Rustenburg in the west. Boers begun to besiege Marabastad fort on 29 December 1880. The three main engagements of the war were all within about sixteen miles of each other, centred on the Battles of Laing's Nek (28 January 1881), Ingogo River (8 February 1881) and the rout at Majuba Hill (27 February 1881). These battles were the result of Colley's attempts to relieve the besieged forts.Although he had requested reinforcements, these would not reach him until mid-February. Colley was, however, convinced that the garrisons would not survive until then. Consequently, at Newcastle, near the Transvaal border, he mustered a relief column (the Natal Field Force) of available men, although this amounted to only 1,200 troops. Colley's force was further weakened in that few were mounted, a serious disadvantage in the terrain and for that type of warfare. Most Boers were mounted and good riders.

The First Boer War was the first conflict since the American War of Independence in which the British had been decisively defeated and forced to sign a peace treaty under unfavourable terms. It would see the introduction of the khaki uniform, marking the beginning of the end of the famous Redcoat. The Battle of Laing's Nek would be the last occasion where a British regiment carried its official regimental colours into battle.

The British government, under Prime Minister William Gladstone, was conciliatory since it realised that any further action would require substantial troop reinforcements, and it was likely that the war would be costly, messy and protracted. Unwilling to get bogged down in a distant war, the British government ordered a truce. When in 1886 a second major mineral find was made at an outcrop on a large ridge some thirty miles south of the Boer capital at Pretoria, it reignited British imperial interests. The ridge, known locally as the "Witwatersrand" (literally "white water ridge" a watershed), contained the world's largest deposit of gold-bearing ore. In 1896, Cecil Rhodes, Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, attempted to overthrow the government of Paul Kruger who was then president of the South African Republic or the Transvaal, The so-called Jameson Raid failed.

By 1899, tensions erupted into the Second Boer War, caused partly by the rejection of an ultimatum by the British. The Transvaal ultimatum had demanded that all disputes between the Orange Free State and the Transvaal (allied since 1897) be settled by arbitration and that British troops should leave. The lure of gold made it worth committing the vast resources of the British Empire and incurring the huge costs required to win that war. However, the sharp lessons the British had learned during the First Boer War which included Boer marksmanship, tactical flexibility and good use of ground had largely been forgotten when the second war broke out 18 years later.

Victorian 3rd Burma Campaign 1885-87. In the 1880s British concerns were raised by contacts between the Burmese and the French whose colonial expansion in Indo-China had reached the Burmese border. When a British company was fined by the Burmese for contraventions of its teak extraction contract, the British demanded arbitration and, when that was refused, issued an ultimatum which would have reduced Burma to a vassal state. When this was not accepted on 9 November 1885 an invasion force under Maj-Gen Harry North Dalrymple Prendergast was sent up the Irrawaddy. At this time, except that the country was one of dense jungle, and therefore most unfavourable for military operations, the British knew little of the interior of Upper Burma; but British steamers had for years been running on the great river highway of the Irrawaddy River, from Rangoon to Mandalay, and it was obvious that the quickest and most satisfactory method of carrying out the British campaign was an advance by water direct on the capital.

Further, a large number of light-draught river steamers and barges (or flats), belonging to the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company under the control of Frederick Charles Kennedy, were available at Rangoon, and the local knowledge of the company's officers of the difficult river navigation was at the disposal of the British forces, hence Victorian use of "gunboat diplomacy". The Burmese king and his country were taken completely by surprise by the rapidity of the advance. There had been no time for them to collect and organize any resistance. They had not even been able to block the river by sinking steamers, etc. Across it, for, on the very day of the receipt of orders to advance, the armed steamers, the Irrawaddy and the Kathleen, engaged the nearest Burmese batteries.

By 26 November the envoys from King Thibaw offered to surrender. Thibaw was taken into exile in India and the British annexed the remainder of Burma on 1 January 1886. Increasing numbers of troops were required to counter the resistance campaign which continued into 1889.

Unrest continued in the northern tribal areas. Well into the early 1890s. Burma was seen as a buffer between India the heart of the British Empire and the French colony of Indo-China, (Vietnam), annexation of Burma to protect the British Empire was therefore considered to be justified. The item "Victoria Zulu 1879 clasp war medal George Slack Royal Scots Fusiliers of Chester" is in sale since Sunday, July 4, 2021.

This item is in the category "Collectables\Militaria\19th Century (1800-1899)\Medals/ Ribbons". The seller is "theonlineauctionsale" and is located in England.This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United Kingdom

- Country/ Organization: Great Britain

- Issued/ Not-Issued: Issued

- Type: Medals & Ribbons

- Conflict: Zulu 1879-1st Boer war 1880s

- Service: Army

- Era: 1816-1913